If you ask focus groups to play word association when they hear the word “transgender,” most audiences will hit a few common themes: “Oppressed,” “discrimination,” “violence,” or “controversial” make frequent appearances, with “isolated”, “suicide”, and “alone” not far behind. Not much changes if you switch between “transgender person” and “transgender youth,” and it remains consistent across racial and educational backgrounds. I’ve heard these words—hidden on the other side of the “glass” so the group of cisgender participants believes they can speak freely with the cisgender moderator where no transgender people can hear them—from both strong progressive audiences who express a great deal of familiarity with trans people and less engaged moderate audiences. I’ll let you guess what conservatives say.

These associations are, by no means, wrong. According to data from the Center for Disease Control & Prevention, transgender youth are some of the most vulnerable young people in the country today. They face higher rates of physical violence, sexual violence, harassment off- and online, and suicidality than their cisgender peers. They’re overrepresented in our country’s youth homeless shelters, juvenile detention centers, and foster care system—themselves frequent sites of abuse and violence. They face not just bullying and harassment from their peers but, like all children, face the gravest risks from the adults in their lives—parents who abuse or reject them, teachers that harass or ignore them, and police who mark them as criminal by virtue of their deviance from gendered norms.

What I have not found, however, is that someone’s familiarity with these very real, well-documented hardships transgender youth face has much impact on their overall support for policies that would prevent that hardship. If trans suffering was going to convince more people to support transgender rights, after all, then it’s hard to imagine what more they would need to see. Not only have trans people been the object of ridicule and ritual shaming across the entire history of mass media, but even the last decade of more sympathetic visibility has long focused on our hardships, our needs, and our traumas.

For 25 years, the most recognized public expression of solidarity with transgender people has been vigils, funerals, and the counting of trans bodies lost to violence. If our protection, safety, and freedom could be won by strictly portraying the consequences we face when we’re denied them, then we’d already be protected, safe, and free.

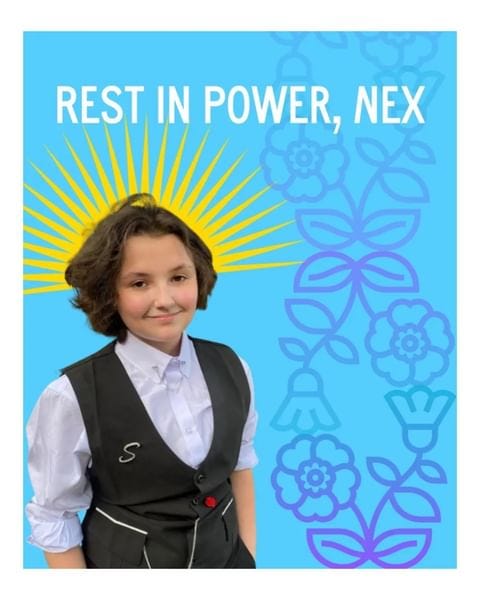

When I first learned of the death of Nex Benedict, a 16-year-old nonbinary Choctaw student at Owasso High School outside of Tulsa, Oklahoma, my first emotional response was a deeply familiar grief. It’s the same grief I felt for Tasiyah Woodland, Ariyanna Mitchell, and Kathryn Newhouse, all transgender teenagers not much older than Nex murdered in the last two years. It’s the same grief I feel for every transgender young person now presented with another fear, another trauma, another reason for the adults in their life to doubt they have a future worth protecting. It’s the grief I feel for the future transgender people deserve, one denied to Nex and one whose possibility will seem even more remote in the wake of their death.

Nex’s generation is simultaneously the queerest generation on record and, not coincidentally, one enduring a nationwide assault on their safety, their health care, and their personhood. Facing the existential threat of an entire generation of children like Nex carving out meaningful, queer lives for themselves free of the rigid patriarchal binaries they hope to enforce, Christian Nationalist politicians and right-wing ideologues are determined to raise the cost trans people pay for being trans and suppress the possibility of those lives—so much so that a dead nonbinary child only confirms for them that their plan is working.

The ongoing escalation of political attacks, violent extremism, and state repression of transgender people seeks to reinforce the widely-held notion that trans lives are unlivable lives—that is, so fraught with risk and danger as to yield nothing but trauma, misery, and chaos. What they’re responding to isn’t any empty show of “visibility” but a specific kind of visibility—one that portrays a transgender life worth living and, therefore, transgender death worth preventing.

In their 2020 book The Force of Nonviolence, philosopher Judith Butler writes about the many ways violence is permitted and excused in a culture and society that supposedly abhors all acts of violence. Among the many acts of erasure, blame, and stigmatization, Butler writes, withholding grief from a person or kind of person is among the most damning and begins long before death itself. To be grievable, Butler writes:

“…is to be interpellated in such a way that you know your life matters; that the loss of your life would matter; that your body is treated as one that should be able to live and thrive, whose precarity should be minimized, for which provisions for flourishing should be available. The presumption of equal grievability would be not only a conviction or attitude with which another person greets you, but a principle that organizes the social organization of health, food, shelter, employment, sex life, and civic life.“

A life denied both the basic needs for life and “provisions for flourishing” is already marked for erasure and dismissal—it is a life that has already been regarded as not “mattering.” Were we to truly grieve Nex Benedict, we would embrace—from the school to the home to the Indigenous community whose dispossession Nex inherited—the most oft-denied principle of reproductive justice, the right to raise a child in a safe and healthy environment.

In order to deem a life worthy of grief, one must consider not only their death a loss but their misery and their pain as avoidable, destroying systems that produce that misery and reorganizing them to ensure not only the egalitarian survival of all people but the conditions and resources they need to thrive and repair for the harm already done.

By almost any measure, transgender youth like Nex are already marked in the eyes of much of the public as ungrievable. It’s why the various fables and nightmares that dominate right-wing agitprop find fertile soil in the minds of the same audiences who nonetheless confess that trans people experience high rates of violence and social marginalization. Denied any positive vision of a transgender life—one where a child like Nex is affirmed in their subjectivity, protected from harm, and guaranteed access to the future they deserved—even sympathetic audiences blame our hardships and our deaths on our defiance of a patriarchal hierarchy they’ve known all their lives.

This illusion holds even as the powers of the state are mobilized in plain daylight to generate that hardship and cause that death. The machinery needed to police gender performance, demand conformity, and either criminalize or pathologize deviance from the norm is obviously man-made yet consistently regarded as ordained by God, nature, or both. The violence, fear, poverty, and shame that trans people experience is a policy choice disguised as an inevitability.

This is a perception that frequently penetrates the psyche of transgender people ourselves, worsening not only our famously high suicide rate but also confirming the fears that keep us in the closet and encouraging us to delay medical and social transitions. After news of Nex’s death spread across the internet, calls to a crisis hotline operated by the Rainbow Youth Project from Oklahoma nearly tripled, with most young people citing Nex’s death and reporting their own experiences with bullying and harassment. We, too, are susceptible to the myth that transgender lives are unworthy of protection—even, and perhaps especially, when that life is our own.

The natural response of many to correct this record—in Instagram graphics and Twitter threads and heartfelt newsletter reports like this one—is to try and rebut these narratives through expressions of “It Gets Better”-style encouragement or public displays of mourning. I’m not so cynical as to believe these gestures are made in bad faith—they are honest expressions of sorrow using a language and schema any person who spent the last decade online will recognize from its repeated use for individual tragedies representative of larger systemic failures. A similar effort followed the death of Brianna Ghey, a transgender girl the same age as Nex whose murder at the hands of her classmates captured a comparable wave of public sympathy in the United Kingdom—even while it did nothing to dissuade the slow march of trans erasure taking over that country’s government and media. Hell, it didn’t even prevent the open mockery of trans people by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak steps away from Brianna’s parents.

Without the material support, protection, and cultural shift that would have marked Nex’s life as grievable before their death, however, these gestures only obscure our collective failure to provide that support to all transgender youth and, truly, all youth, period. Without an organized effort to make our communities, our schools, and our homes places where transgender youth thrive, then all the vigils and mourning are worse than a charade—it is a ritual designed to absolve ourselves of blame the next time a young life is taken.

There are people across the country who are doing that work. There are activists, organizers, parents, and educators in Oklahoma who fought for Nex and continue to fight for all children like them. There are organizations like Freedom Oklahoma and leaders like Rep. Mauree Turner who will do everything in their power to ensure no trans person feels they are destined for a similarly tragic fate and every member of their community knows their life is worth protecting while they are still living it. They will do so even as many liberals write off queer life in red states like Oklahoma as too risky, portraying the only solution as relocating and pursuing queer life elsewhere—thereby reinforcing the same myth that allowed Nex to die in the first place.

But the kind of political movement needed to repel the many legislative attacks in Oklahoma and across the country—to say nothing of establishing the systems of care and community needed to ensure every life is valued—will need more people, more resources, and far less apathy.

“It is notoriously difficult to get the message across that those who are targeted or abandoned or condemned are also grievable,” writes Butler, “that their losses would, or will matter, and that the failure to preserve them will be the occasion of immense regret and obligatory repair.” Repair for a tragedy such as the death of Nex Benedict cannot come strictly from the punishment of the peers who attacked them a day before they died, the school officials who decided not to call an ambulance, or the doctors who allowed them to go home and sleep with an apparent head injury. It can’t stop at shaming Ryan Walters, the superintendent of Oklahoma schools who has decided to build his career on the misery of children like Nex and families like the Benedicts, nor the Oklahoma state legislature moving more anti-transgender bills shuttering the future Nex deserved than any other state.

Repair can only come from all those who have remained silent in the face of a coordinated effort to deny transgender people the freedom to be themselves—Not as shame and derision but as an invitation. Their sorrow at the death of a child is necessary, but the conclusions they’re likely to draw from it are perverse. We need them not to lament for a past they will never get back but demand a future that we all can reach.

“In Greek tragedy,“ writes Butler, “lament seems to follow rage and is usually belated. But sometimes there is a chorus, some anonymous group of people gathering and chanting in the face of propulsive rage, who lament in advance, mourning as soon as they saw it coming“

Thank you Gillian for this. As a grandparent of a non-binary child, and a non-binary transfemme person myself, I was deeply affected by the senseless death of Nex.

The children who bully are simply the proxies for the adults who know no better than to sow hate. Transpeople have become pawns by politicians to distract their followers from the real problems they face.

Gillian, this was really beautiful. Thank you for putting so much thought and heart into words for our community. We really need this right now.