What you likely remember from the climactic monologue delivered by Barbie audience surrogate Gloria (played emphatically by America Ferrara) is the lengthy list of contradictions women are expected to straddle in Western culture. “You have to be thin, but not too thin,” Gloria tells a room of discarded Barbies. “And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin. You have to have money, but you can’t ask for money because that’s crass. You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean. You have to lead, but you can’t squash other people’s ideas. You’re supposed to love being a mother, but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time.”

It’s an unfortunately familiar list of grievances, one that displays the many things that haven’t changed since Barbie was introduced more than sixty years ago while highlighting the ever-tightening corset strangling women held to impossible standards of life, love, career, family, and self. Appropriately enough, the monologue–delivered by a woman, to a room full of women, in a movie made by, for, and of women–begins with a deceptively complex truism: “It is literally impossible to be a woman.”

It seems such a strange thing for a woman to say. She is, after all, “be-ing” a woman as she says it. How could it be impossible to be something you are actively in the middle of being? What about womanhood allows you to do it while finding the task not merely Sysiphean but actually beyond one's grasp?

“To be a woman is to be an actress,” wrote Susan Sontag in 1972, the same year Barbie evolved opposable thumbs. Perhaps the 20th century’s most famous women intellectual, Sontag often seemed begrudged by the title “woman,” refusing invites to events focused on women and only rarely commenting on the surge of second-wave feminism that overlapped with the criticism and writing for which she is best well known. Those scant writings have been collected and published earlier this summer in a new edition called On Women, rendering the subject abstract for analysis as surely as she did style, interpretation, and camp.

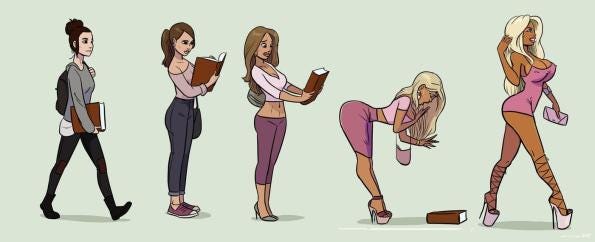

“Being feminine is a kind of theater, with its appropriate costumes, decor, lighting, and stylized gestures,” she writes in “The Double Standard of Aging,” a bromide against misogynistic derision of women who refuse infantilization published when Sontag was on the verge of 40. “From early childhood on, girls are trained to care in a pathologically exaggerated way about their appearance and are profoundly mutilated (to the extent of being unfit for first-class adulthood) by the extent of the stress put on presenting themselves as physically attractive objects.” This pressure forces women into a permanent state of self-judgment, and, by Sontag’s reading, self-involvement, so much so that “a woman who is not narcissistic is considered unfeminine” and one who succumbs to these pressures of aesthetic labor is doomed to become a “moral idiot.”

Barbie, as Greta Gerwig’s new blockbuster movie is well aware, has long been the defining pinnacle of that pressure, the example by which all who seek entry into the category of “woman” are judged. One could easily define misogyny as the proportional punishment handed out based on the distance between you and the model set by Barbie, a thin white blonde woman who, as Gloria says in the movie’s aforementioned monologue, manages “to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line.”

Barbie, like womanhood, is impossible. Not just her physical proportions–which are famously so out-of-whack no one is quite sure where she keeps her liver–but also the “accomplishments” and “careers” for which she is occasionally hailed as a feminist hero. A list of her past and present job titles ranges from President to Rockette, rapper to babysitter, matador to Starfleet engineer officer. She’s competed in the Olympics across eight sports, was an ambassador to UNICEF the same year she was an Army officer in Desert Storm, and mastered veterinary medicine for pets, ponies, and pandas.

You couldn’t achieve Barbie’s many lives any more than you could achieve her measurements. Both her lived life and physical embodiment are beyond your reach in this or any lifetime. To be held against such an unreachable standard, by others or oneself, is a deeply unfair proposition that can and often does manifest in subjugation, alienation, and violence. Your likelihood of facing any of those outcomes is determined by how far you fall from the example she sets, rendering her a plastic tool in the hand of a patriarchal system keen to define womanhood by force of law while declaring it inevitable and natural. For many who encountered her as children, Barbie is a lifelong rejection of their own subjectivity in favor of an artificial and ever-moving goalpost erected in defense of the oldest hierarchy known to man and the first many seek out to bring order to their social reality. She is, from the perspective voiced by Gloria’s daughter Sasha in the Barbie movie, “a fascist.”

Which is why, I suspect, Barbie cries. In the film, the titular Barbie–”stereotypical Barbie” as she’s known and portrayed by Margot Robbie–begins experiencing deviations from her perfect life and body. She’s overcome by depression and existential dread. She starts developing cellulite and grows uncomfortable in heels. Where she once floated angelically toward the ground when descending from her dream house, she is now yanked to the floor by the inevitability of gravity. Surrounded by the knowledge her perfect life and self are not being reflected in the lives of real women and girls–that she is a reminder of the impossibility of womanhood–Barbie wept.

What Barbie experiences is a speedrun of many women’s journey from the ideal of girlhood to the reality of aging. Though Barbies do not procreate (the ever-pregnant Midge is separated by both her name and her negative space in the movie’s script) Barbie dolls are functionally fertility idols, restrained to the ages when most women can procreate and thus are deemed ripe for exploitation by patriarchal capitalism and the men who benefit from it. Beauty is then defined by a woman’s ability to match these standards of youth. “Only one standard of female beauty is sanctioned,” writes Sontag, “The girl.”

Girlhood is ephemerality yearning for immortality; womanhood is a reality forced into a race against an impossibility. When Gloria says “It is literally impossible to be a woman,” she means “literally” literally. The boundaries of womanhood as defined by a patriarchal society are so small that no person could actually fit inside of them yet its demands are so large no person could hope to fill them. To redefine these boundaries based upon one’s own subjectivity is to defy the myth they are a biological inevitability, a truth so dangerous the institutions that profit off that myth will spare no expense towards tightening the restraints. “No one rests,” the fictional CEO of Mattel played by Will Ferrel orders his corporate minions, “until this doll is back in the box.”

The movie Barbie could easily be read as an ode to the box. The release of the Barbie movie followed a surround-sound buffet of product endorsements and brand deals marketing the film and its cotton candy appearance. As Jessica DeFino noted following the film’s release, these promotional partnerships ranged from the predictable nail polish and lip gloss to blonde hair dye, teeth whiteners, “bikini serums,” and (to emphasize the many ways Barbie’s femininity is a very white one) skin lightening creams. “If the Barbie production ‘speaks directly to women … about the impossibility of perfection,’ as the New York Times Magazine insists,” writes DeFino, “its products speak directly to women about the importance of attempting it anyway.”

This is hardly a new trap laid for women and feminist criticism. Writing in, of all places, Vogue in 1975, Sontag noted “beauty is a form of power” but lamented that “it is the only form of power women are encouraged to seek.” She goes on to speak to the same understanding of womanhood’s impossibility raised by Gloria’s monologue in the Barbie film (emphasis mine):

“To preen, for a woman, can never be just a pleasure. It is also a duty. It is her work. If a woman does real work-and even if she has clambered up to a leading position in politics, law, medicine, business, or whatever-she is always under pressure to confess that she still works at being attractive. But insofar as she is keeping up as one of the Fair Sex, she brings under suspicion her very capacity to be objective, professional, authoritative, thoughtful. Damned if they do, women are. And damned if they don't.”

Sontag prescribes as the solution to this dilemma as “some critical distance from that excellence and privilege which is beauty, enough distance to see how much beauty itself has been abridged to prop up the mythology of the ‘feminine.’ There should be a way of saving beauty from women and for them.”

In the most sympathetic interpretation, Barbie does just this, offering a celebration of femininity ostensibly removed from its patriarchal trappings. Barbieland is coated in pink and pastels while nonetheless presented as a matriarchal utopia. The Barbies are fitted in high fashion with permanent smiles on their faces, but also accept their Nobel prizes without the mandatory apologies and forced humility that so often follow women’s accolades. They don the drag of womanhood while lacking the reproductive function and subservience to male authority that, in patriarchal society, defines womanhood.

Whether the aesthetic of femininity can be separated from, and celebrated despite, the coercive means many women are forced to perform femininity is a longstanding and debatable question, one raised by drag queens and transgender politics as surely as it’s raised by Dolly Parton, Sex and the City, and the fashion industry itself. In her famous 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” (published the same year Barbie was first granted bendable legs), Sontag raises as examples the “corny feminine flamboyance” of Hollywood movie stars like Jayne Mansfield and Betty Grable, their exaggerated performance of womanhood emphasizing the aspect to which all womanhood is a performance. “Camp sees everything in quotation marks,” she writes. “Not a lamp, but a ‘lamp.’ Not a woman, but a ‘woman.’”

In an interview published ten years later, Sontag praised the camp sensibilities of male homosexual culture specifically and its promise for “ironic resurrection” of femininity and the presumed monopoly on it held by women assigned as such from birth. “The parodic rendering of women” she notes, “usually left me cold. But I can’t say that I was simply offended. For I was often amused and, so far as I needed to be, liberated.”

Liberated! She continues: “I think that the camp taste for the theatrically feminine did help undermine the credibility of certain stereotyped femininities–by exaggerating them, by putting them between quotation marks.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

In ironic beauty–that which defies expectations or the role for which it is usually proffered–Sontag saw an opportunity: “Ironizing about the sexes is one small step toward depolarizing them.” In his encyclopedia of camp aesthetics, the British art critic Philip Core would define camp as “the lie that tells the truth,” the exaggeration of a style that emphasizes the degree to which it is a style rather than an inevitability. “Camp is an art without artists,” writes Core. “Camp is gender without genitals.”

Barbie is, in a literal sense, gender without genitals. Both the Barbies and the Kens emphasize gender as performance, archetype, and style. Indeed, much of the film's drama centers on Ryan Gosling’s Ken discovering and distributing the ideology of the patriarchy, erasing the indifference with which Kens are treated in Barbieland and replacing it with subservience to their presumed authority (the Barbies, after all, never forced Kens into submission the way the Kens eventually do to the Barbies). As their loyalty to the patriarchy grows, so, too, does the Kens’ exaggerated performance of masculinity–athletic dominance, denim and leather, Matchbox 20, The Godfather, horses.

When the Barbies–through the tactical deployment of their exaggerated gender performance–take back Barbieland, it’s not clear the men necessarily need to give up that performance with their dominance. “To be honest,” says Gosling’s Ken, “when I found out the patriarchy wasn’t about horses I lost interest.”

Allan, the apparent gender outlaw played by Michael Cera as the only male non-Ken, likewise asserts his masculinity while simultaneously allying himself with the revolutionary troupe of Barbies waging a quiet war on the reign of the Kens. If masculinity can be separated from the violence and injustices of dominance, so, too, can femininity be separated from the violence and injustices of subservience.

In fact, it may need to be. Wandering any city this weekend, you likely saw crowds of women and girls clad in hot pink–perhaps people of other genders joining them–and delighting in being outwardly, proudly feminine whether as a communal act, a reclamation, or a bit. And this is hardly specific to the Barbie movie; Taylor Swift’s record-breaking Eras Tour has likewise inspired a mass embrace of the feminine, the girly, the pink and pastel and glittery. As Michelle Goldberg writes, the success of both Barbie and Swift emphasizes “there is a huge, underserved market for entertainment that takes the feelings of girls and women seriously. After years of Covid isolation, reactionary politics, and a mental health crisis that has hit girls and young women particularly hard, there’s a palpable longing for both communal delight and catharsis.”

People denied femininity–by virtue of their race, their weight, their assigned gender, or any other disqualifying attribute that separates them from the white, blonde ambition of “stereotypical Barbie”--know all too well femininity’s allure. So, too, do fascists, revanchists, and anti-feminists who often attempt to grasp femininity and further cement its attachment to subservience and complementarianism. Many chapters of Phyllis Schlafly’s coalition to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment flew the banner of “women who want to be women,” positioning themselves in opposition to a supposed effort by feminists to erase femininity and replace it with a bland, enforced gender neutrality; Their present-day descendants range from “trad wife” Instagram influencers and online outrage factories like H. Pearl Davis.

There’s a reason, after all, Margot Robbie was deemed fit to play both this ostensibly-liberated Barbie and, in the 2019 film Bombshell, a Fox News anchor. Conservatives and fascists recognize gender performance as a powerful packaging for traditional gender roles. When the Kens take over Barbieland, they face remarkably little pushback from the Barbies who willingly give up their power and even seem to relish in their submission. “It’s like a spa day for my brain,” says one Barbie reflecting on how little anxiety she feels without needing to make any decisions for herself.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Disentangling femininity from submission and instead embracing it as an act of autonomy and independence is no mere hypothetical prescription for feminist liberation–it’s a reflection of how many people do embrace femininity as a style and mode of living. In that same Vogue essay on beauty, Sontag notes the efforts of 1960s feminists to take “against the way the conventions of beauty reinforce the image of women as indolent, smooth-skinned, odorless, empty-headed, affable playthings.” This often meant a condemnation of the “artificial” and a deification of the “natural”--unshaved legs and armpits, bare faces free of makeup, and Black hair neither dyed nor straightened. But this adherence to the natural, Sontag notes, “still competes with other ideas of beauty that remain influential and movi ng…’natural’ is beautiful, but so is ‘unnatural.’” A rigid adherence to what is deemed appropriately “natural” can be as oppressive as a rigid adherence to artifice, femininity is neither exclusive to nor excluded from either category. “Fantasy proliferates. Change is a constant.”

Gender performance is labor, but so is art. It can be compelled and coerced in ways subtle and explicit, yet likewise punished and censored when it defies existing power. As much as femininity–and, for that matter, masculinity–must be saved from the tradwives and alpha males, so, too, must it be extracted from the capitalistic impulses of Barbie, fashion, or other aesthetic industries. Femininity is powerful not because, as Goldberg writes, it can move markets. Femininity is powerful because of the people it speaks to, the experiences it invokes, and its potential as a style towards collective protection and reclamation of self-determination.

Womanhood under a capitalist patriarchal society is an impossibility on purpose. Much like capitalism’s mandate for eternal growth, the impossible metric of womanhood is meant to create a demand for ever more labor and ever more consumption. The feminine ideal represented by Barbie is no more reachable than the satisfaction pursued by those who seek ever-growing piles of wealth. A paranoid reading would throw out femininity with this impossible standard, deeming it irredeemably tainted by its association with such vast and violent institutions. But as its mass appeal suggests, a different angle is needed, a reparative reading that finds the power of femininity in the dreams and creations of women and takes back from those institutions something free, genuinely unlimited, and beautiful.

As a woman in middle age, I feel like I am *just finally* coming to terms and in comfort with my own femininity, and (perhaps sadly?) a lot of that stems from being in the age demographic that suddenly makes you less visible or entirely invisible to many men.

You might think feeling "unseen" by men might hurt my self esteem, but at this same time I find that OTHER WOMEN (even younger women) have been so kind and generous in ACTUALLY SEEING ME in a way that feels genuine and taking the time to let me know they see and LIKE how the outfit I've put together is a reflection of my personal style and my sense of self, even though nothing I own or wear is probably what would be considered "style" in a more mainstream sense.

i really appreciate the way you navigated this. from the framing (especially for those of us who haven't seen the movie), to the conversation about the performance of gender & feminity in particular, to the role that camp & drag both engage & inform gender. i didn't think id make it through a barbie thinkpiece but this was time & energy well spent. well said.