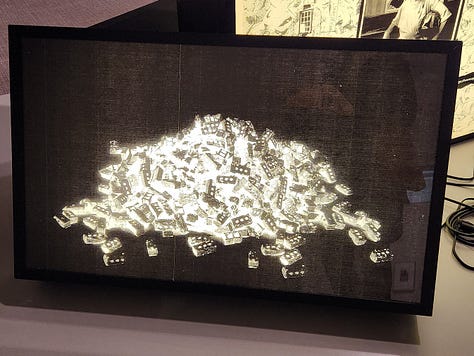

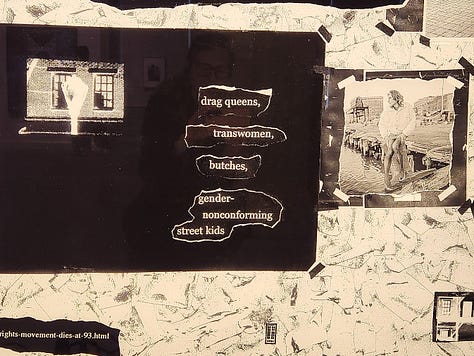

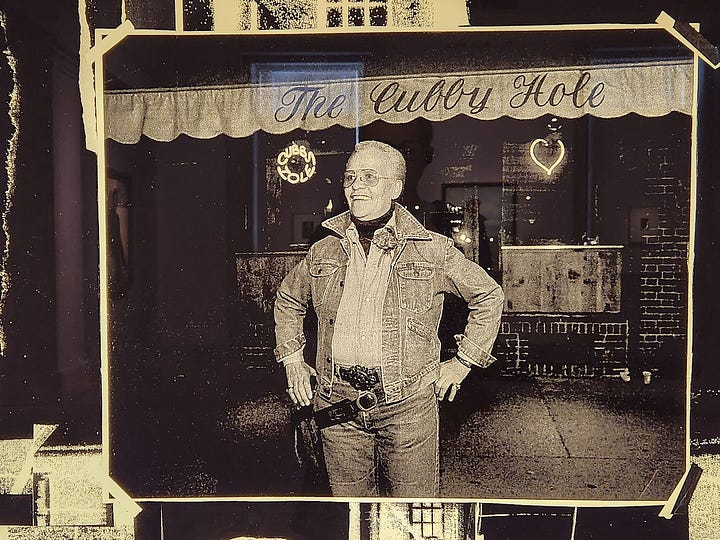

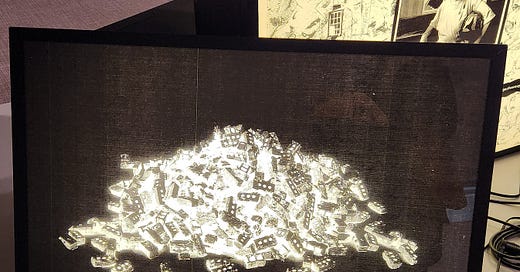

If you make your way to the second floor of the National Portrait Gallery in DC right now—walking past all 44 ex-presidents and their oily, hagiographic tributes—you’ll quickly find your way to Stormé at Stonewall, an installation by textile artist LJ Roberts consisting of a set of electric light boxes arranged on the ground and flickering light into the gallery. Printed onto the lightboxes are colleges of photographs and newsprint focused on the life of Stormé DeLarverie, the multiracial butch lesbian and drag king often credited with instigating the resistance to police at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village one night in the summer of 1969. The collages use text and quotes about DeLarverie and Stonewall as well as photos of the bar itself and its now most famous regulars, Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson.

As is common with historical events and historical figures, the rough edges of the Stonewall story—one about police violence, street kids, sex work, and class resistance—have been sanded down to fit into liberal narratives of eternal progress. One wonders how many of the poor and persecuted people who engaged in the weeklong rebellion on Christopher Street would feel hearing it being honored today as a lesson learned by corporations, police departments, and even presidents in their inauguration speeches. One is particularly struck by the canonization of Marsha P. Johnson and her STAR co-founder Sylvia Rivera as the patron saints of an LGBT movement for legal rights like marriage, even though their class politics and commitment to revolutionary action suggests they had more in common with the Black Panther Party than anything like GLAAD or the Human Rights Campaign.

Much like the memory of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black civil rights movement, the gentrified version of the stories of Johnson, Rivera, DeLarverie, and the Stonewall scene is ripe for appropriation because of its theatrics, its attractive sense of defiance, and the vagueness of confirmed facts about who was there and how they lived their lives before and after the events (the neighborhood around Stonewall in Manhattan would be devastated little more than a decade later by the height of the AIDS crisis). This includes efforts on all sides to draw clear identity categories onto the bodies and lives of people who intentionally defied it, whose understanding of their relationship to femininity or masculinity was more varied than any one label could do justice.

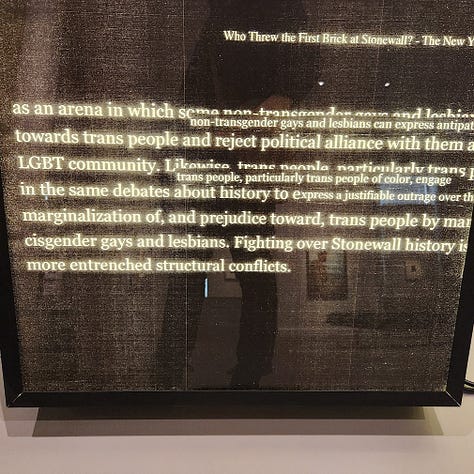

Alongside quotes from interviews with DeLarverie, Roberts’s installation includes spliced-up segments of a 2016 New York Times story about considerations then being made by the Obama administration to honor the Stonewall Inn as a national landmark. The original text of the story spoke exclusively of gay men’s involvement in the uprising, an error amended by the correction that there was “at least one lesbian involved.” Marsha P. Johnson is mentioned but as a drag queen which, while not inaccurate, is at least an incomplete description of someone who also described herself as a woman, was referred to with feminine pronouns by most of those who knew her, and spoke about taking hormones to feminize her body. DeLarverie, who was famous in the scene and identified by witnesses on the first night on June 28, is not named in the story at all.

As the Portrait Gallery’s plaque next to the installation notes:

“Roberts noticed DeLarverie’s absence in narratives about the rebellion, including news coverage of the Stonewall National Monument designation. In response, this installation features images of DeLarverie from different stages of her life, photographs of other queer activists of color, including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, and collaged articles that transform information into poetry. Fractured, flickering, and expansive, the work refuses the static singularity of the conventional monument. Instead, it offers history as an ongoing process of construction.”

When news spread last night that the National Park Service had removed any mention of the words “trans” or “transgender”—including the “T” in any variation of the LGBT acronym—my mind immediately lept back to my first visit to the Portrait Gallery after Roberts’s installation was added in 2022. I was struck by the irony of the installation’s placement at the exit of the presidential portrait gallery where a large photographic portrait of Donald Trump looked on, now replaced by a photo of Joe Biden (I assume because the gallery doesn’t host portraits of current presidents). That a president who previously sought to define transgender “out of existence” in his first term would be positioned over a work dedicated to historical erasure seemed more fitting than ironic, as if it were a comment on the same kind of erasure that Roberts sought to comment on.

Storme at Stonewall is a visitor’s introduction to a section of the gallery called The Struggle for Justice, where one will find portraits of activists, organizers, and those who “worked to advance the status of women, racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and persons with physical and intellectual differences.” Wrapping Roberts’s work are portraits of Stokely Carmichael, Yuri Kochiyama, Sarah Schulman, Alice Wong, and members of the Young Lords, most of whom understood themselves as Marxists, communists, or militants. It’s possible many, if not all, of these activists would resist the canonization now faced by Johnson and Rivera (the latter of whom had her own portrait added to the gallery in 2015).

But as the plague at the gallery entrance notes, “the struggle to expand inclusiveness has become the defining characteristic of democracy in the United States.” Inclusion, then, is supposed to tell a story not so much about the person or event being included but the country doing the including, weaving their actions and biographies into a fabric that includes the presidents lining the walls in the gallery prior. The adoption of Stonewall as another chapter in the American story is surely meant as a statement of optimism, that a movement for “progress” or “inclusion” can win by seeking entry into the version of the American history America likes to tell itself. But one thing most people seem to agree about the people at Stonewall that night in 1969 is that they were not seeking out “inclusion” into anything. Mostly, throwing bottles and bricks at the police trying to arrest and beat them, they wanted to be left the fuck alone.

But if inclusion of trans people like Johnson and Rivera is meant to tell a story about America, what story do we hear from their exclusion? Specifically, what story is told by the erasure of their identities as trans women?

To start, it’s hard to prove Rivera or Johnson were at Stonewall on June 28, 1969, but they were well-known figures in the scene that erupted that night. It’s also hard to prove they would have identified themselves as “transgender,” a word that was coined ten years earlier but wouldn’t come into common use until the 1990s. Rivera and Johnson variously described themselves as “gay,” “drag queens,” “girls,” “women,” “transvestites,” and eventually (from an interview Rivera gave in 2001) “transgender.” Like many other terms for sexual and gender identities—homosexual, bisexual, transsexual—transgender, too, was born from the medical sphere and transformed by the social, its boundaries loosened and stretched to describe a broad range of statuses and conduct. Its retrospective application to historical figures—from Joan of Arc to Louisa May Alcott—is often controversial. But Rivera, Johnson, and many other street queens in and around Stonewall that night were at the very least trans femininized—that is, punished by virtue of their feminine performance in defiance of their male gender assignment.

As Jules Gill-Peterson writes in The Short History of Trans Misogyny, trans feminized figures in activism and organizing were quickly sidelined by gay movement organizers keen to achieve inclusion by appearing almost invisibly gay (“virtually normal” as Andrew Sullivan would put it a generation later). People like Johnson and Rivera were not only unsightly to these activists but brought along a Marxist vision of politics that made it unlikely they would ever, say, collaborate with police departments or seek inclusion in the U.S. military. Johnson and Rivera only founded STAR after feeling betrayed by the Gay Activists Alliance and ensuing pride parades, a split made famous by a speech delivered by Rivera in 1973 damning the cis queers present for abandoning those abused and raped in jail. “The increasingly gender-normative gay and lesbian movement reasoned that if they sold out the queens,” writes Gill-Peterson, “they might be welcomed into a sanitized, middle-class version of citizenship from which they used to be excluded.”

This divide, which keen observers will see flare up occasionally, has never truly been along sexual or gender lines (LGB vs. T so to speak). Rather, it’s most frequently been a divide over class, with those most able to obscure their difference from the straight world pushing aside those queers whose ”fracturing, flickered, expansive” appearance and demeanor might push them away from domestic, bourgeois life. Far from an abstract debate over “assimilation” or aesthetics, this same fault line would be enflamed over and over again not just in the face of trans feminity but promiscuity, nonmonogamy, and proximity to sex work, all of which are shaped by (and shape in return) one’s ability to make a living, start a family, sustain housing, and avoid criminalization.

This has continued even as the radicalism of people like Rivera and Johnson has frequently been cited favorably people forms of activism that wanted nothing to do with Rivera and Johnson’s politics. As Rivera told one interview in 2001 (a year before her death), “I gave you your pride. But you have not given me mine.”

This, to me, is what the erasure of “transgender” is meant to offer to the country. If our previous inclusion by the National Park Service and institutions like the Smithsonian was meant to assure America that everything will work out fine the more people we include—that there is enough space on the gallery walls for all of us—our exclusion is meant to tell a tale of scarcity. The defining feature of Trumpism is that other people’s suffering will be your gain, and it’s a theme told across anti-trans agitprop (one reason why our inclusion in athletics has proven sticky even for people eager to conceive of themselves as good-hearted liberals). It’s why they can only perceive the removal of racist barriers as “anti-white racism” or will object to even the most basic displays of inclusion that are not for people like them. They have no concept of their own pride that is not based in denying someone else’s theirs. It’s what the scholar Arlie Russel Hochschild literally calls a “pride economy.”

Though some are shocked by the visceral language used in Trump’s executive orders to demean trans people, this rhetoric and the policies backing them are an effort, as Gill-Peterson said of previous efforts to exclude trans people, to define the boundaries of citizenship itself. The argued endpoint is not that trans people do not exist as trans but that our existence is devious, errant, wrong, and far from worthy of dignity. Trans feminine people are not “newly visible” since 2010—we’ve been objects of scorn and mockery in mass media as long as mass media has existed. But inclusion in the story the country tells about itself is a dangerous affront to the narrow, supremacist vision of American citizenship the administration wants to define for all.

As I watched online reactions to NPS’s edits to their commemoration of Stonewall, the most common refrain was along the lines of “trans people have always been here” or “a world without trans people has never existed and never will.” Some criticize this popular message as a means of establishing validity for trans identities through a historical record that has only recently begun to admit the existence of a people called trans, stating that our right to healthcare and self-identification should not be predicated on our pre-existence. In their contribution to the anthology Feminism Against Cisness, the historian Beans Velocci notes, “The insistence on trans people always having been here is an ironic one, given that the whole point of transness is that your past doesn’t have to dictate your future. Legitimacy doesn’t come from having always been one thing.”

I think that mistakes the value people get from these refrains or stories of bygone queers lifted out of erasure. The notion that “trans people have always been here” is not a bid for legitimacy—it’s a fact of our resilience. It’s a fact that anywhere that gendered lines have been drawn by states and authoritarians, there have been people defying and crossing them. Like the cops at Stonewall, the Trump administration are not enforcing anything as abstract as the boundaries of our identities. What they’re horrified by—existentially threatened by—is our respect.

Gillian, you are such a great writer and thinker. This, combined with your other essay, is especially good because it shows why people, besides being craven, and inconsistent with any defensible value system, are mistaken in a self-defeating way to be indifferent to transgender rights and freedoms. Divide and conquer is their strategy! Your essay goes along PERFECTLY with Silvia Rivera’s speech which remind me of ‘ain’t I a woman?’ in a certain way—which is that she was there sharing the brunt of what our morally corrupting views on other humans results in, and had been beaten and had her nose broken and they should rip the blinders off and see her but their vision is directed the wrong way. They are still holding up the hierarchy but they should rip the whole thing down and throw it away instead of thinking they can get something out of it.

It will turn against them. Nothing has proved that freedom is always in peril unless everyone has it than this period we’re in.

It makes me very angry on her behalf and it makes me love her. She is truly everything that heroes are made of. She sees clearly like Sojourner Truth did, and all the brutality in the world couldn’t shut her up (and of course that’s no recommendation for brutality, or to imply that’s what everyone should be like—we can’t be. Just that this is how some people are made, and without them certain truths about humanity would never come to light.)

This always get to me where people love the heroes later, when everyone approves of them, and it’s safe to love them. They let them suffer, and then they bask in their self-regard for that valor whenever that valor is safe to approve of. When these same people are being shredded, and there is some cost to standing with them, they turn away like cowards or else want to dictate terms to protect any slight advantage, and keep other people under the yoke. It prolongs other people’s agony if they don’t want to hear the truth —suffering they are responsible for, and it eviscerates any claim they have to decency. But the truth is the truth, and it condemns them. Spineless bigot Seth Moulton thinks some child should be hampered for life because of his competitive feelings about children’s sports, and personal delusions? The people with eyes to see all know what he is now. Who else wouldn’t he fuck over for his momentary feelings and his delusion that depriving someone else puts his children at an advantage? People like him show they would always go along with any systemic injustice because their thinking is totally imbued with a commitment to it.

Very well written—thank you.