Between Reproductive Past and Trans Future

19th century abortions in Arizona, 21st century sex changes in England

This week, two sobering developments for reproductive rights and bodily autonomy proved William Faulkner right: “The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past.”

On Tuesday, the state Supreme Court of Arizona revived a near-total 1864 abortion ban, ruling the law was newly enforceable in the state following the U.S. Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade. The law is one of several across the country first enacted in the middle of the 19th century, passed by all-white and all-male legislatures before nonwhite, nonmale people could vote amid nativist fears of non-Anglican immigrants “replacing” white demographic power. That they are being revived amid another time of racist fears of migrants and declining birth rates only emphasizes the vital role reproductive coercion plays in those xenophobic nightmares and how tightly racial supremacy is still threaded throughout nearly every aspect of American identity.

On Wednesday, meanwhile, a review of gender-affirming medical practices for transgender youth in England seemed to offer a roadmap for a world without transgender youth in it. While offering a relatively mixed bag of common-sense recommendations for expanding access to hormone therapies (such as opening regional “hubs” for care to meet expanding demand and conducting more clinical research), the review—authored by Dr. Hilary Cass who previously consulted with the state of Florida in their effort to ban care for trans youth and mostly ban it for trans adults—simultaneously urges “extreme caution” for prescribing puberty blockers and claiming “for most young people, a medical pathway will not be the best way to manage their gender-related distress.”

Although the report found medical treatments were only provided to 500 British kids a year with extensive assessment (an average of over six in-office visits just to start treatments), low rates of detransition (0.5%), and not a single patient rushed into treatment without assessment, such broad diagnostics claiming the empirical evidence for gender transitions is of “poor quality” (a term it doesn’t define) have been greeted by those calling for the abolition of youth gender medicine as nothing short of complete vindication.

That’s because the Cass Review rejects the affirming model of care embraced by groups in the US like the American Psychological Association or the American Academy of Pediatrics and instead openly regards medical transitions as an unjustifiable last step to be pursued after blaming a child’s gender nonconformity on anything and everything else—social influences, comorbid mental health disorders, or the influence of social media among them. Contrary to its stated aims, the Review further pathologizes gender nonconformity itself, claiming “social transitions”—which can be as simple as a new haircut and clothes—”may change the trajectory of gender identity development” and thus should be avoided, a slippery slope argument that suggests letting your son play with Barbies will invariably lead to a vaginoplasty so best to hand him the monster truck and nip it in the bud.

Most tellingly, the review claims limiting access to hormone treatments for adults may be advisable, theorizing “a follow-through service continuing up to age 25 would remove the need for transition at this vulnerable time and benefit both this younger population and the adult population.” The overall recommendation is to force patients to wait through psychological busywork and relevant-sounding delays, implementing a largely-arbitrary set of hoops to jump through with the hopes the patient just gives up. Focus on the patient’s anxiety, focus on their autism, focus on any other issue except their gender and their desire for a sex change because, as private British medical provider GenderGP said of the report’s underlying assumptions, “cisgender lives are judged to be more valuable or desirable than transgender lives and that healthcare services should prioritise encouraging youth to assume cisgender lives, regardless of the suffering that this causes.”

To anyone familiar with the complicated history of transgender medicine, the incentives, definitions, and assumptions of the Cass Review are quite familiar. For much of the last century, access to cross-gender hormones and surgeries was regarded by doctors as a last resort for any patient transgressing their gender assignment, measures to only be pursued if the patient’s gender nonconformity persisted after extensive and frequently violent forms of conversion therapy. Sex changes were not an act of autonomy for the patient as much as proof of the doctors’ ability to divine their patient’s “true sex” with the patient mostly getting in the way.

As Barry Reay details in their seminal Trans America: A Counter History, many of the leading figures in transsexual medicine from the 1950s through the 1970s shared Dr. Cass’s paternal condescension and open contempt for their trans patients. Where Dr. Cass seems to suggest gender transitions are a distraction from other comorbidities (rather than, as it was for myself, an important step along the path to addressing them), 20th century doctors condemned trans patients for the same, blaming their gender incongruence for their failure to meet a middle-class lifestyle or even, on occasion, the doctor’s own standards of attractiveness for their patient’s new gender.

As Reay chronicles, one Johns Hopkins psychologist derided his trans patients as “devious, demanding, and manipulative,” blaming their downtrodden fate in society on an “impairment in the neuropsychological mechanism that mediates the experience of falling in love.” The urologist Elmer Belt found his trans patients “were so unsuited to handle the problems of life itself that changing their sex organs was not a satisfactory solution of their troubles with society.” The author of one the earliest studies of transgender men wrote harshly of their “serious personality disorders” and “rigid defense structure,” recommending extensive psychotherapy in place of hormones or surgery. Such “therapy” was frequently brutal and practically carceral—One 1961 case study detailed by Reay included a lengthy regime of forced vomiting, nausea, and headaches induced intravenously via apomorphine while the patient was shown photographs of their transvestism.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

As late as 1973, a supposed “cure” for transsexuality received a glowing report in The New York Times, where the reporter Jane Brody—who covered transsexual health care for a decade without, best I can tell, ever speaking with a trans person—waits until the 9th paragraph to describe the horrifying maltreatment offered in this case study of a 17-year-old. The Times writes:

“The boy [sic] was first conditioned to stand, walk and sit in a more masculine manner, then taught to speak with a deeper voice and less feminine inflections. The therapists then tried to change his sexual fantasies, lavishly praising the patient's successful substitution of female for male figures. Using so‐called aversive techniques, such as mild electrical shocks, the therapists were then able to diminish his sexual response to pictures of nude men. The successive treatments were carried out over a 10‐month period.”

The success of these treatments, as the Times put it, was proven when the victim “had returned to his high school and acquired a steady girl friend.“

In 1979, the pioneering Johns Hopkins gender clinic made an abrupt about-face, shuttering their doors and encouraging dozens of other clinics to do the same. The cause was a Cass Review-style paper published by Dr. Jon D. Meyer which, while conceding sex change surgeries were “subjectively satisfying” to trans people ourselves, did not lead to “rehabilitation” in terms of “jobs, educational attainment, marital adjustment, and social stability.”

As G. Samantha Rosenthal notes in her recent essay on the historical roots of today’s backlash, the Meyer study “assigned points to patients who were in heterosexual marriages and had achieved economic security since their operations” while issuing demerits for “gender nonconformity, homosexuality, criminality, or [seeking] mental health care.”

These were not only far from “objective” standards—to counter the “subjective” satisfaction of trans patients—but also impossible ones for most transgender people living in the 1960s and 1970s. Crossdressing was still illegal across much of the country, sex work was even more heavily policed than it is now, and even the burgeoning gay rights movement viewed “drags” as an open threat to their quest for mainstream respectability.

For Meyer to demand social and economic stability from a group intentionally and universally denied it was Kafkaesque at best then—and remains so now. As Rosenthal writes:

In requiring trans patients to enter straight marriages and hold gender-appropriate jobs to be considered successful, Meyer and Reter’s study was homophobic and classist in design. The study exemplified the pseudoscientific beliefs at the heart of transgender medicine in the 1960s through the 1980s, that patients had to conform to societal norms – including heterosexuality, gender conformity, domesticity and marriage – in order to receive care. This was not an ideology rooted in science but in bigotry.

Much like those greeting the Cass Review as confirmation of their own biases, the Meyer paper was attractive to many leaders in the medical field as a foundation for reasserting their own paternal authority over the “subjective” happiness of their patients, leading dozens of gender clinics across the country to shutter their programs. The affirming model was sold to these clinics as a means of converting deviant and sexually confused men and women into productive, heterosexual women and men, and measures of success were, like the Cass Review, heavily rooted in standards far from the objectivity the Meyer paper claimed to defend.

That patients were “subjectively satisfied” mattered little—to many of these doctors, the Meyer paper confirmed their fears that the entire affirming model was just letting patients run the asylum and that they were wrong ever to supplant their own “objective” authority—however rooted in homophobia, misogyny, and other bigotries it may be—with the “subjective” need for autonomy among transsexual people.

Since the Meyer paper, a decades-long shift away from medical paternalism across the entire field of medicine and towards collaborative, patient-centered health care provided an opening for transgender advocates to reclaim their own agency as patients and subjects. As I wrote a few weeks ago , these efforts to expand access and move towards both an affirmative model for transgender youth and an informed consent model for adults ran parallel to similar efforts to narrow racial gaps in health outcomes, embrace neurodiversity models of mental health, and expand access to abortion, contraception, and other reproductive health care. This is a democratic vision of medicine that doesn’t disregard empirical measures but, in fact, acts in their defense. These advocates rightfully recognizes that standards of evidence often regarded as “objective” are frequently enough built on the subjective biases of researchers and practitioners and the subjectivity of patients is a necessary corrective.

Clearly, however, many politicians and right-wing activists are eager to have the medical state return to its role as a reliable partner for eugenic social engineering, closing paths toward “subjective satisfaction” and forcing patients towards rigid, essentialist understandings of not only who gets to be a man or woman but what men and women are for. You see this not only in the Cass Review nor just in regards to transgender medicine; it was a rife theme in the Supreme Court filings and arguments over the FDA’s approval of the abortion drug mifepristone, where a conservative set of doctors—one of whom also authored Indiana’s ban on gender-affirming care—demanded the return of restrictions against the drug which advocates long-held were based in stigma, not evidence.

Which brings me back to that 1864 Arizona abortion law. Bans like Arizona’s came amid a contested effort in the US and the UK by strictly male physicians to limit the practice and reach of female midwives, asserting masculine authority over the feminine collective will in order to shut down women’s control over their own reproductive lives. In her newly-prescient survey When Abortion Was A Crime, historian Leslie Reagan notes “much of the regulation of abortion was carried out not by government agents, but by voluntary agencies and individuals. The state expected the medical profession to assist in enforcing the law.”

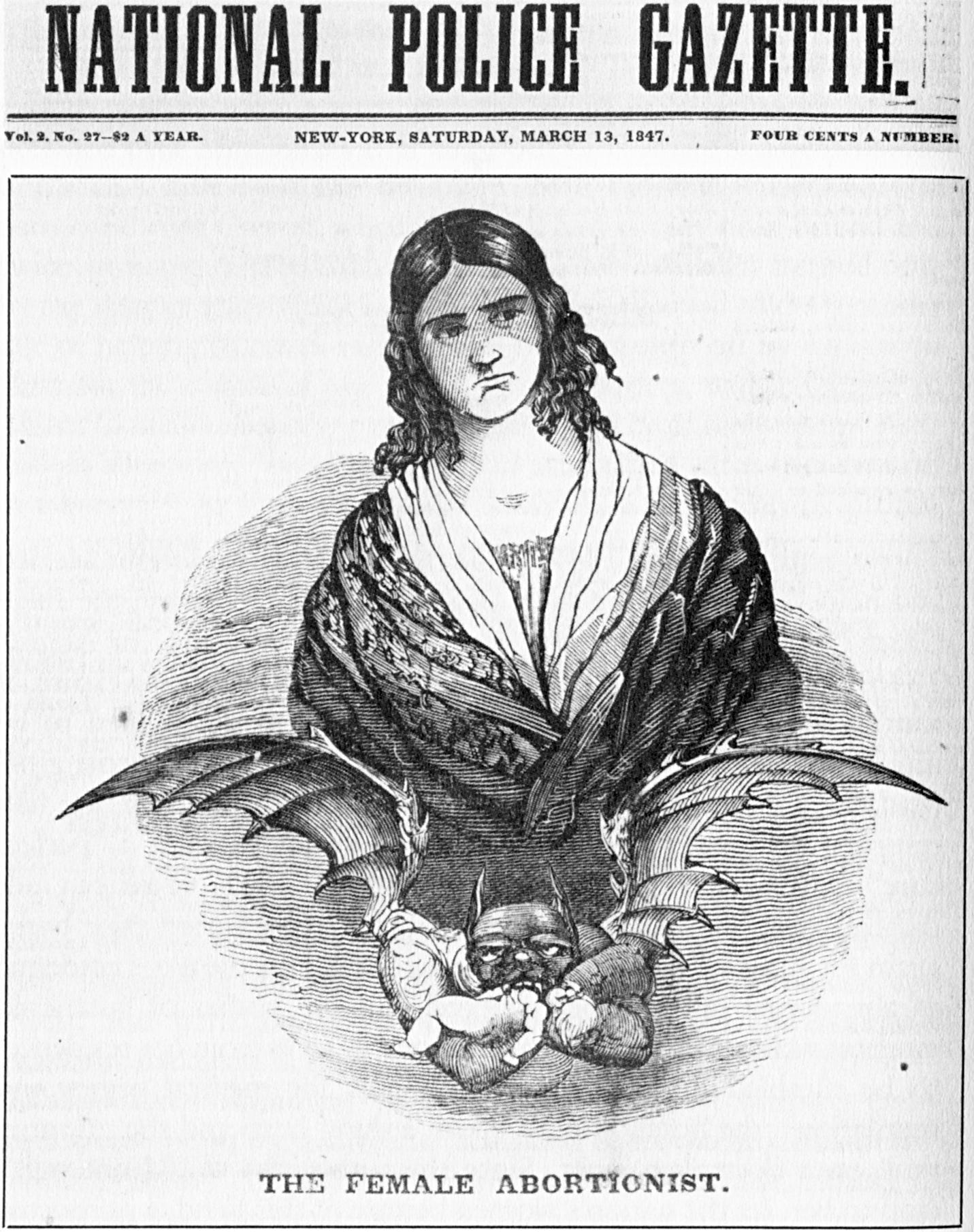

When the American Medical Association first launched in the 1840s, helping the state ban abortion was among its top priorities in what Reagan calls “an alliance between medicine and state.” Much like Republican state legislatures and Attorneys General targeting providers of transgender health care today, “state officials won medical cooperation in suppressing abortion by threatening doctors and medical institutions with prosecution or scandal.” To ward off state action, the AMA devoted early issues of JAMA to scandalizing known abortion providers and publishing lengthy deathbed testimonies of women killed by faulty surgical abortions. The media played its part, too—Reagan recounts the role of the Chicago Times in running in-depth reports about abortion clinic raids or “seedy” underground abortion networks.

It’s hard not to see these patterns in The New York Times sensationalized coverage of gender medicine—either from the 1970s or today—and politicized investigations by Attorneys General in Texas, Missouri, and Tennessee, and threats of prosecution under 24 statewide bans passed in just the last three years.

Little wonder why some providers, as the Campaign for Southern Equality has found, doctors and medical providers in the United States are going beyond the scope of recent bans on youth gender medicine to shut down care even when legal. While some doctors, like apparently Dr. Cass, are simply nostalgic for a time when they were the sole arbiters of the direction a person’s life or body should take, others are facing the prospect of state repression and complying well in advance at the expense of their patients’ freedom and well-being. Much like the medical state and political state of the 19th century joined forces to squash women’s agency over their reproductive lives, those very same institutions are speedrunning the same process against transgender youth in the 21st.

I read the Cass Review in a St. Louis hotel room the night before I attended (in my day job) an en banc hearing of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals over Arkansas’s ban on gender-affirming medical care, the first such ban anywhere in the developed world. While many states have since tried to justify their own bans by pointing to European reviews of gender medicine that preceded the Cass Review, Arkansas (and 23 other states that have since joined it) stand alone among liberal democracies in banning this care outright, finding their only corollaries in autocratic states like Hungary and Russia (which have simultaneously restricted abortion, demonized migrants, and enforced a coercive natalism designed to boost the “right” birth rates).

Arkansas’s law was the focus of a two-week trial in the fall of 2022, during which medical providers, bioethicists, researchers, and four families with their transgender youth spoke cogently and emotionally about this care, the evidence that supports it, the misinformation that surrounds it, and how it has served as the foundation for the lives of their patients and their children. Only one transgender person testified during the whole trial—a sober, wholehearted 17-year-old named Dylan Brandt. It was an emotional but gratifying experience, affirming to hear not only the breadth of evidence supporting this care aired out in court but also four families confident in their love for their children and the future they deserve.

In June of last year, the District Judge who oversaw that trial overturned the law, an appeal of which was the subject of this week’s hearing in the Eighth Circuit. Notably, the attorney representing Arkansas told the panel of ten judges this week that the state contested none of the factual findings in the District Court’s opinion—including that “transgender care is not experimental care,“ “adolescents are able to understand the risks, benefits, and alternatives to a medical intervention,” “the body of medical research as a whole shows that gender-affirming medical treatments are effective at improving mental health outcomes for adolescents with gender dysphoria.” and “for those adolescents who are already being treated with puberty blockers or hormone therapy and who would be forced to discontinue treatment, experts on both sides agree that the harms are severe.”

The state doesn’t claim banning this care is in the best interests of transgender children—it simply asserts nothing in the Constitution prevents it from doing so. This is why transgender people’s autonomy will either spring from our own humanity and subjectivity or not at all: That right is limited when it is only granted with the blessing of pathology because, when asked to choose between their relationship to power or their relationship to their patients, many doctors like Dr. Cass will go leaps and bounds to choose their power over their patients.

For much of the cisgender public—and even some trans advocates—that may come as a surprise. Gender transitions are understood as the treatment for a condition called gender dypshoria rather than a human right. And while the distress and dissociation that we call “dysphoria” is real, gender dysphoria’s existence as a diagnosis is simply the key that unlocks the cage transsexual people are put in to deny us autonomy over our own bodies, tying us to the conditional good will of a biased and compromised medical state. As the late trans femininist Rachel Pollack said almost thirty years ago (emphasis mine),

“A number of transsexual and transgender people have suggested that people seek surgery because of pressure from the medical profession, which convinces them that surgery will allow them to become normal members of society. I cannot believe this. I have met too many transsexuals who know very clearly that surgery is exactly and precisely what they want, and that the doctors are not their masters but their instruments.”

As Leslie Reagan notes, the era between 19th century abortion bans like Arizona’s and Roe was not abortion free—doctors simply worked alongside the state to decide who was and was not deserving of the right to end their pregnancy as much as eugenicists decided who should or should not have children, denying abortions to “immoral” white patients as surely as they forced sterilizations onto Black, immigrant, and disabled patients. With the rise of psychiatry—itself a state partner in policing women and queer people—this even included “therapeutic abortions” granted when a woman threatened suicide in much the same way gender-affirming medical care is thought of now as principally a means of suicide prevention. Both abortion and sex changes do, in fact, prevent suicide—but your autonomy should be granted long before a doctor agrees the denial of it might end your life.

The doctors who wish to once again be the masters of their abortion patients are now limited to the few cranks and conservative activists who would sign up to overturn the FDA’s approval of mifepristone. Because transgender people’s autonomy challenges more assumptions about gendered life than abortion does, however—negating not just patriarchal power but the naturalized gender binary that serves as its foundation—and transgender people ourselves are still denied representation among the decision-making institutions that govern this care, the doctors running that playbook against us are welcomed as liberators by media outlets and politicians already convinced a transgender life is an unlivable life.

As much as 19th-century gatekeepers couldn’t fathom a woman that would want to end a pregnancy in the absence of a life-threatening emergency, 21st-century gatekeepers still can’t fathom the desire to change one’s sex—particularly when the world still treats trans people like shit. Our “subjective satisfaction” is thus steamrolled by supposedly “objective” measures constructed around that failure of their own imagination, our misery living in a transphobic world treated as simply yet another reason to do away with transsexual life altogether.

I keep telling people that this is the best trans newsletter they're not (yet) reading.